St. Catherine’s Court, Buffalo, New York, courtesy of Google maps, August 26, 2023.

In basic terms, cul-de-sac means “bottom of a sack,” from the Latin culus, “bottom.” For the purpose of this essay, my definition of modern cul-de-sac is a dead end street terminating in a loop, resembling a lollipop on a map, lined by (usually) single-family homes on spacious lots, with no commercial, industrial, or agricultural uses. Cul-de-sacs used to be discouraged in urban street design, as per this 1904 code from England, unless necessitated by topography. This changed with the mass adoption of the automobile.

In American city and town planning, Radburn, New Jersey, designed in 1928, is generally considered the birthplace of the modern cul-de-sac. Designers Clarence Stein and Henry Wright used them extensively to separate foot traffic from automobile traffic. Radburn was heavily studied and imitated from then on. Cul-de-sacs, loops, and curvilinear roads replaced grids as the dominant American residential development pattern.

The Urban Pattern, 6th ed., 1993, p. 308.

Reilly, William. Design of Urban Streets, p. 3-15. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, 1980.

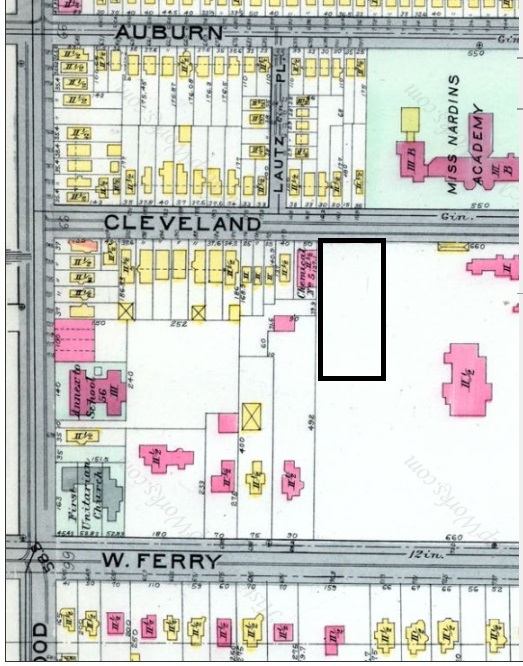

St. Catharine’s Court in Buffalo’s Elmwood Village neighborhood was laid out in 1921-1922, a full seven years before Radburn. Below is the approximate site in 1915. This parcel was originally part of the John J. Albright estate at 730 West Ferry Street. Albright’s mansion, the large brick (pink) structure at the center right, was demolished in 1934. Lautz Place is now Cleveburn Place.

New Century Atlas of Buffalo, 1915, vol. 1, plate 18, courtesy of the New York Public Library. Yellow means wood frame; pink means brick.

The developer of both St. Catherine’s Court and Tudor Place, the side street immediately to the east, was the Niagara Finance Corporation (NFC). It may have been headquartered in Welland, Ontario, Canada, according to incidental mentions in Google Books of a Niagara Frontier Company. It did not turn up in the New York State corporation database.

The land was purchased from the Albright estate around 1921. The name was apparently chosen in honor of St. Catherine’s Court in Bath, England, which served as the model for John J. Albright’s Tudor-style mansion.

This author was unable to locate any surviving business records from the Niagara Finance Corporation. Such records might help illuminate all who were involved in this project and how they arrived at the cul-de-sac design, as opposed to simply cutting a street all the way through from Ferry to Cleveland Avenues like they did with Tudor Place.

Buffalo Courier, January 24, 1922, p. 3

According to Buffalo Common Council Proceedings, the NFC deeded St. Catherine’s Court to the City of Buffalo on May 24, 1922. The local representatives, presumably also partners, in the NFC were attorney Bradley Goodyear (1885-1959) and his brother Anson Conger Goodyear (1877-1964), one of the founders of the Museum of Modern Art. According to Who’s Who in Finance, Banking, and Insurance, Anson was the president of the NFC:

Leonard, John, ed. Who’s who in finance, banking and insurance, 1923-1924, p. 330.

The Gurney & Overturf real estate firm handled the sale of lots. This company survives today as Gurney, Becker & Bourne.

Buffalo Courier, February 14, 1923

Below is St. Catherine’s Court in 1935, built out except for two house lots to the east. The Albright mansion has been demolished and his estate subdivided into smaller house lots. Tudor Place to the east was cut through from Ferry to Cleveland in 1922, at the same time that St. Catherine’s Court was developed.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Buffalo, Erie County, New York, Vol. 5, 1935, p. 442. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

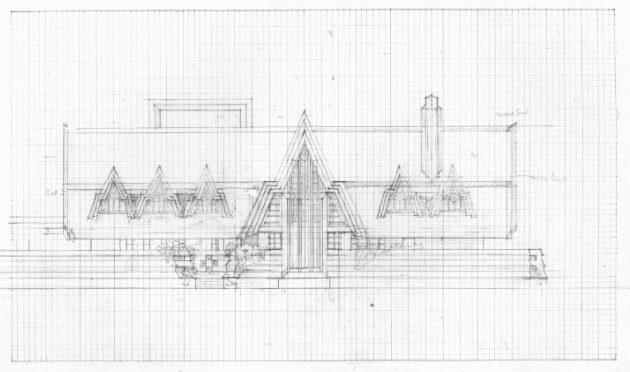

St. Catherine’s Court almost had a Frank Lloyd Wright house. At the southeast corner of St. Catherine’s and Cleveland Avenue is a home built by Dorothy Martin Foster (1897-1980) and James F. Foster, Jr. (died 1955). Dorothy was born Dorothy Martin, the daughter of Wright client and patron Darwin D. Martin (1865-1935). Wright designed this house for the young couple in 1921:

Dorothy Martin Foster house (Buffalo, New York). Object title: Elevation, [1921]. Drawing number: 2305.003. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art; Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). House was never built.

The Fosters did not share Darwin’s taste in architecture and hired Harold LeRoy Olmsted to build this Tudor Revival instead. Completed in 1924, it was the high style of the day. It still stands.

Home of Dorothy (Martin) Foster and James Foster, 12 St. Catherine’s Court, Buffalo, N.Y. Collection of University Archives, State University of New York at Buffalo. Date unknown.

If your city or town has a modern cul-de-sac that was built before 1922, please drop me a line!

Footnote: On August 15, 2023, I asked ChatGPT for the earliest American cul-de-sacs. Here is its quote in italics. I looked at the plans of these developments. I saw lots of curvilinear streets and loops but not modern cul-de-sacs.

“It’s important to note that the term “cul-de-sac” as we understand it today might not have been commonly used before 1929. However, there were certainly street layouts and designs that resemble cul-de-sacs in older neighborhoods. Here are a few examples:

- Frederick Law Olmsted’s Suburbs: Frederick Law Olmsted, a prominent landscape architect, designed several planned communities with curved streets and park-like settings that had layouts resembling cul-de-sacs. Examples include Riverside, Illinois (incorporated in 1875) and Druid Hills, Georgia (developed in the late 1800s).

- Llewellyn Park, New Jersey: Llewellyn Park, designed in the mid-19th century by Alexander Jackson Davis and Andrew Jackson Downing, is often considered one of the first planned residential communities in the United States. It features a circular layout with a central park area and radiating streets, somewhat resembling a cul-de-sac layout.

- Lake Forest, Illinois: Established in the 1850s, Lake Forest features winding, tree-lined streets that create a sense of seclusion and privacy, reminiscent of a cul-de-sac design.

- Pacific Palisades, California: This community in Los Angeles was developed in the early 1920s and features curved streets that sometimes terminate in open spaces or dead ends, resembling cul-de-sacs.

- Alhambra Tract, Phoenix, Arizona: This early 20th-century residential development features curved streets and dead ends that could be considered early forms of cul-de-sacs.

Remember that while these examples have elements similar to cul-de-sacs, the term itself might not have been in common use during that time, and the designs might not have all the modern characteristics we associate with cul-de-sacs today. Street layouts evolved over time, and the concept of cul-de-sacs became more standardized as urban planning practices developed.”

Discover more from BuffaloResearch.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.